Bauhaus Octopus X

Ulrike Buck at Triumph Gallery Moscow

Exhibition text by Sandra Meireis, architecture theory scholar in Berlin

In the Bauhaus Manifesto Walter Gropius stated that '[a]rchitects, sculptors, painters,

[…] all must return to craftsmanship! […] There is no essential difference between

the artist and the artisan. The artist is an exalted artisan. Merciful heaven, in rare moments

of illumination beyond man's will, may allow art to blossom from the work of

his hand, but the foundations of proficiency are indispensable to every artist' (Weimar,

1919). This expressionist quote bears witness to a disbelief in technology, this

was then in reaction to the unmediated horrors of WWI. Later, in the Principles of

Bauhaus Production (Dessau, 1926) Gropius departed from the Arts & Crafts credo

and pleaded for strong unity with technology, incorporating industrial progress into

the school's design thinking. As a result, the Bauhaus movements' approach to democratic

design has made global history as a German export hit; in its spirit, other design

schools came into being and multinational corporations spread ready-to-assemble furniture

all over the world. It is also the name giver to a German self-service hardware

store, founded in 1960. This was during the early days of the digital revolution, paralleled

by the rise of DIY culture in the Western world. Thus a certain utopian idea

from the early 20th century has successfully descended into today's reality.

Here, the choice of classic building materials, like terracotta, (wire enforced)

glass and steel, predetermine the set of possibilities for the shaping and emergence of

new objects. The utopian character of traditional crafting encounters the contemporary

living conditions of a digital nomad. Material knowledge is used as an essential

precondition for thinking with and creating through the body and hands, understood

as a sensory extension of the artist's mind – a significant anthropological constant

throughout human history.

Also Octopus vulgaris – one of the oldest living creatures – literally thinks

with its arms: Each of its eight tentacles is equipped with a cloud of neurons that

builds-up different brain fields. Belonging to the Cephalopod species, this softbodied

sea animal emerged in the history of evolution 550 Million years ago, on the cusp

of the Cambrian. Since then the octopus is a mediator between worlds, communicating

between the shallow seawater and the deep sea, one of the most unexplored

and pristine territories on Planet Earth and symbolic of the human subconsciousness.

This solitary animal is a maverick, endowed with three hearts, reason, memory, and

personality. It is capable of camouflaging itself, adapting not only its skin colour and

texture, but also its body shape and behaviour; a complex organism with no clear

brainbody boundary. Diving into its habitat is like diving into the origin of us all,

as Peter Godfrey Smith recently put in his book Other Minds. The Octopus, the Sea

and the Deep Origins of Consciousness (New York, 2016), in which the author tries

to assess their intelligence and challenges science to re-frame its understanding of the

human brains. Correspondingly, the octopus has become an object of investigation in

recent developments in robotics.

The symbolism of the octopus is manifold. Its overall gestalt, its shape and

character is soft and fluid. Lined with countless suction cups, the ceaseless movement

of the intangible tentacles embraces the observer with its mystical, and possibly lethal

beauty. Throughout art history, the octopus conveys indefinite erotic imaginaries, for

instance, in The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife, a woodblock print by the Japanese

artist Hokusai (1814). Thus, it can be interpreted as an allegory of female dreaming,

representing an embodiment of the stream of consciousness method; reactive, intuitive,

associative, and of a sensuousrational nature. Not least, it is said, that the tentacles

motif has been inspirational for the characteristic design of the ancient Minoan

labyrinth. This is one of the most legendary architectural structures in Greek mythology,

keeping the Minotaur imprisoned and proving Ariadne's ingenuity.

The symbol X is universal. Although it is frequently used to indicate a concept

of negation, refusing, dividing, or terminating something; it has much more power

as a positive sign: Primarily it symbolizes the union of two things, expresses their

interconnectedness, or multiplication, lately used in netspeak as symbol for kissing.

It is an indicator, identifier, mark or placeholder, often representing the unknown,

e.g. locating the final destination on a map, where the treasure is buried. Altogether

X stands for the crossing of boundaries, as it is the ancient symbol for change and

transformation. It is also Osiris' symbol, the Egyptian god of the afterlife, and underworld,

the god of resurrection. In pagan belief, witches cross fingers to focus and hold

magical or demonic energy at the point of intersection. This was thought to mark a

concentration of good spirits and served to anchor a wish until it could come true. In

genetics, without the X-chromosome there's hardly life, and the double X designates

the female cell. Not least, the X axis represents the horizontal in the coordinate system.

In the exhibition Bauhaus Octopus X, the X also stands for the multiple interconnections

and mutual enhancement of the material when combined with artistic energy.

The pieces are corpora delicti of a specific moment in time, historically and

biographically, a synthesis of the artist's personal anthropological archive. Aesthetically

the objects amalgamate the ascetic, functionalist Bauhaus style with a postmodern

idea of a networked world-organism. The deployed technologies, such as

sandblasting, iron bending, and clay firing, correspond to the classical elements earth,

wind, and fire, and hence convey an archaic understanding of the world, when senses

were essential for survival. As in Plato's Timaeus (360 BC) where the creation of the

world's soul is manifested in the letter X.

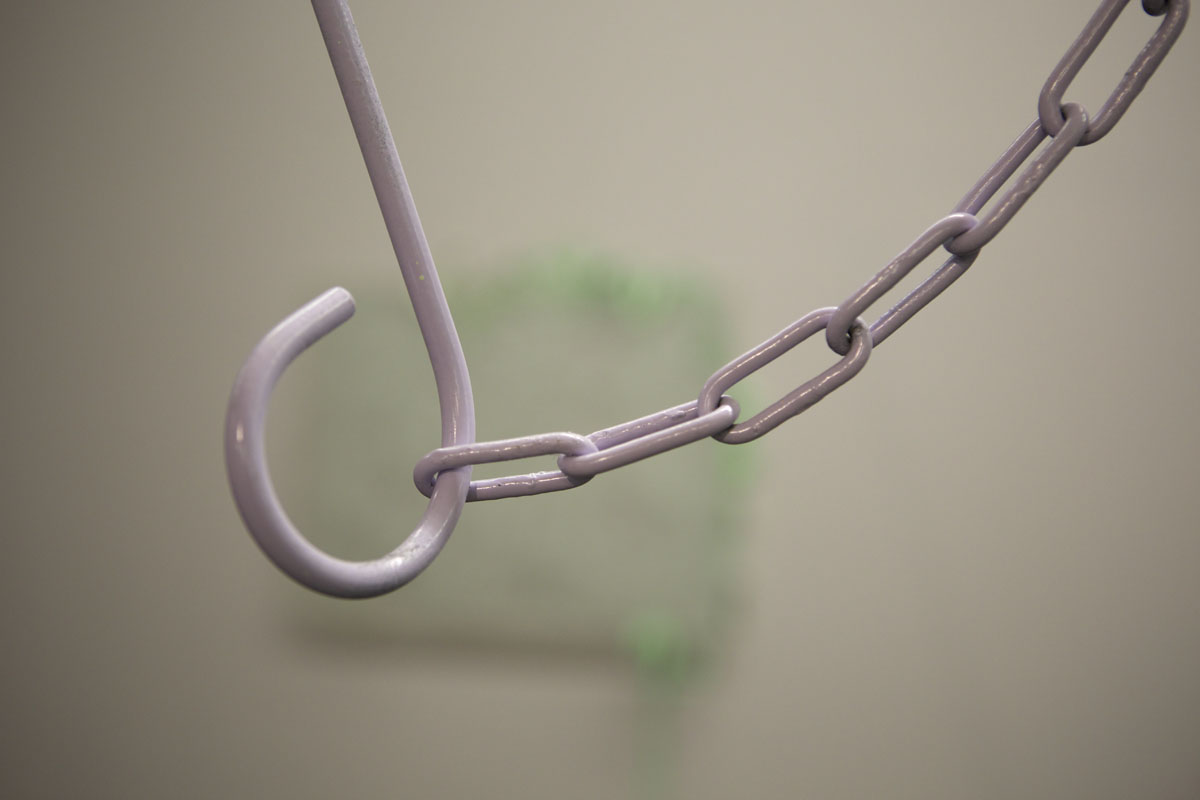

Installation view, Bauhaus Octopus X, Triumph Gallery Moscow 2017

Baushaus Octopus X installation view, Triumph Gallery Moscow 2017

Baushaus Octopus X installation view, Triumph Gallery Moscow 2017

Installation detail with seal. Glazed ceramic, sand blasted wire glass, steel, latex, carpet.

Molluscs

Transparently glazed red ceramics on found rug from russian tool store (150x150 cm)

Molluscs (detail)

Transparently glazed red ceramics on found rug from russian tool store (150x150 cm)

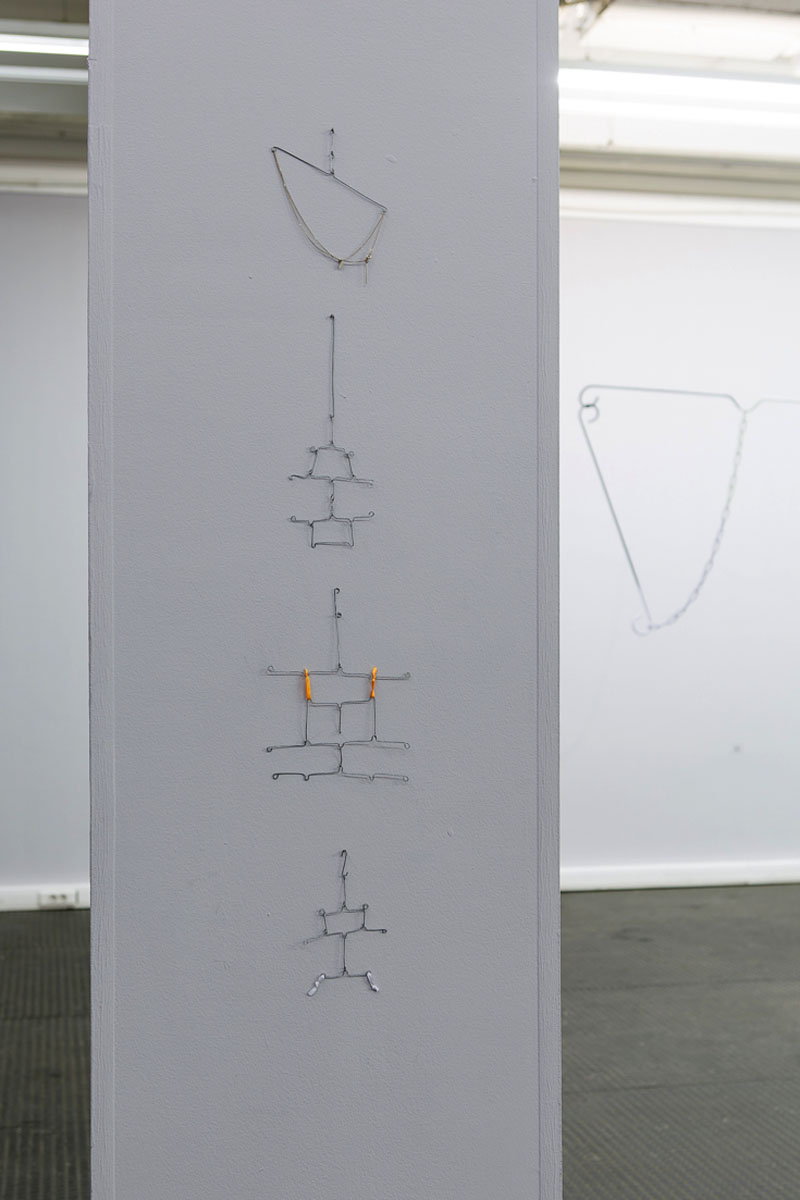

wire models for suspension sculptures

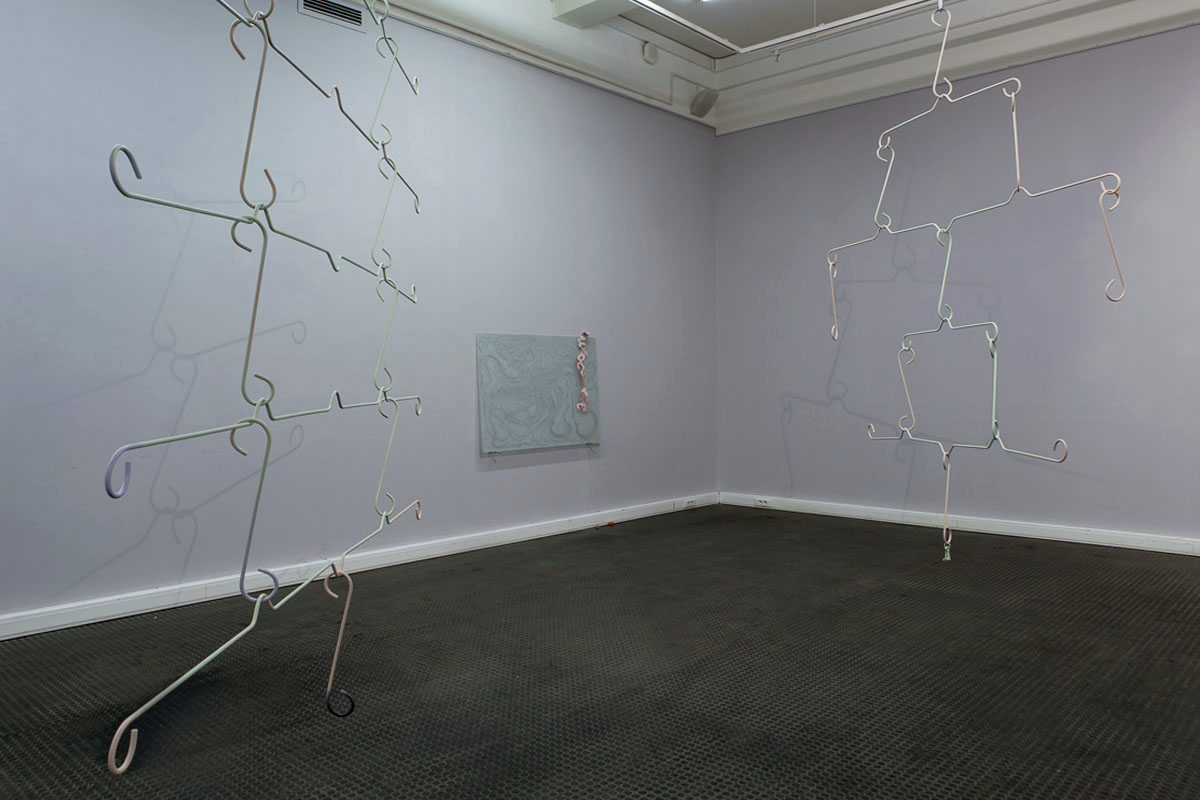

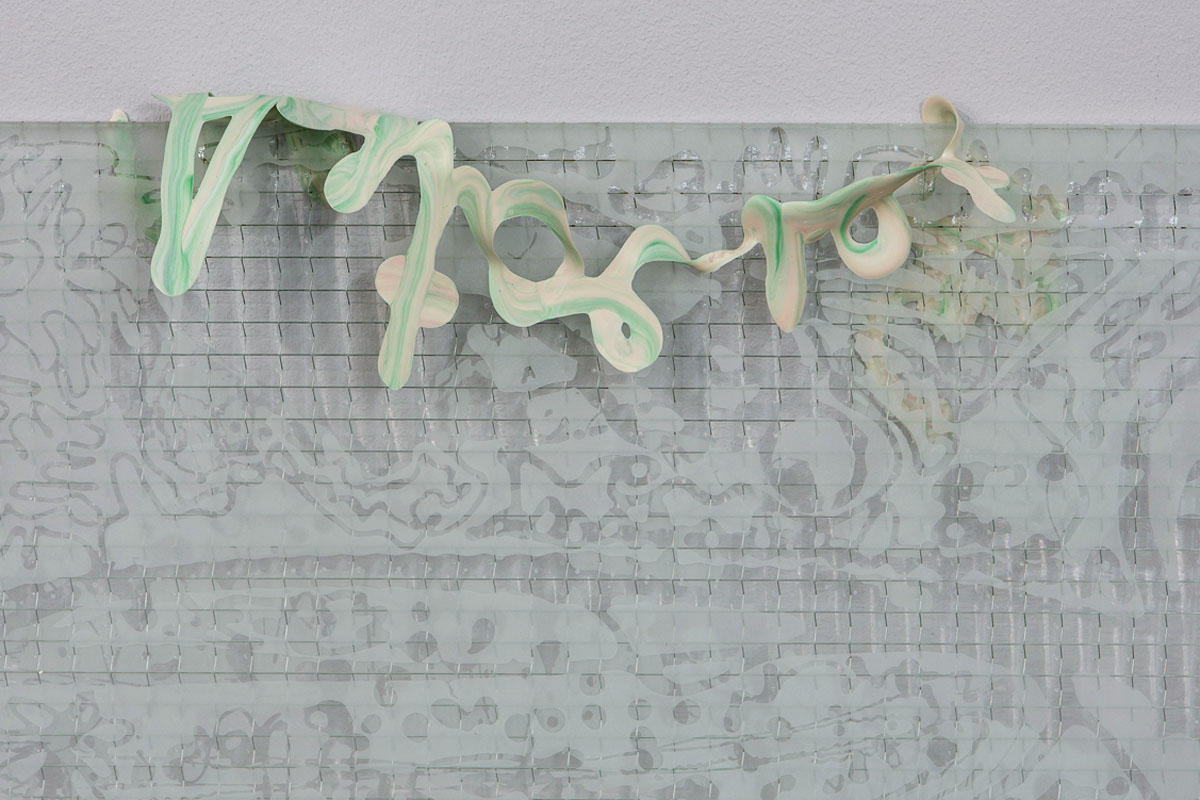

Bauhaus Octopus X, installation view.

Suspensions, hand bent steel rods, latex calligraphy, chains

background: Autoerotic, sandblasted octopus painting on wire enforced glass with latex calligraphy

2017

Bauhaus Octopus X, installation view. Hand bent steel rods, latex calligraphy, chains

background: Autoerotic, sandblasted octopus painting on wire enforced glass with latex calligraphy

2017

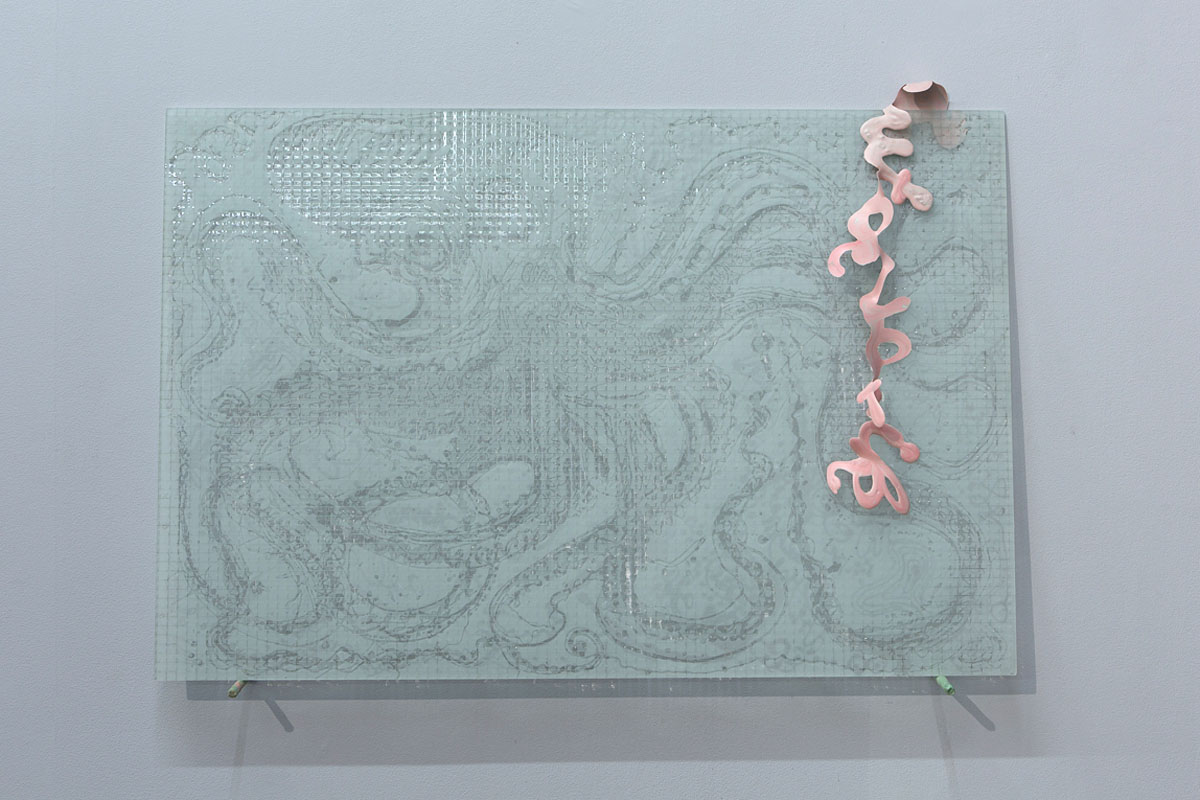

Autoerotik

latex calligraphy and sandblasted painting on steel enforced glass, 2017

Bauhaus Octopus X, installation view, hand bent steel rods, latex calligraphy, chains

background: Tentaclelove, sandblasted painting on wire enforced glass with latex calligraphy

Bauhaus Octopus X material detail. Autoerotic latex calligraphy, sand blasted painting on steel enforced glass, 2017

Bauhaus Octopus X material detail. Autoerotic latex calligraphy, sand blasted painting on steel enforced glass, 2017

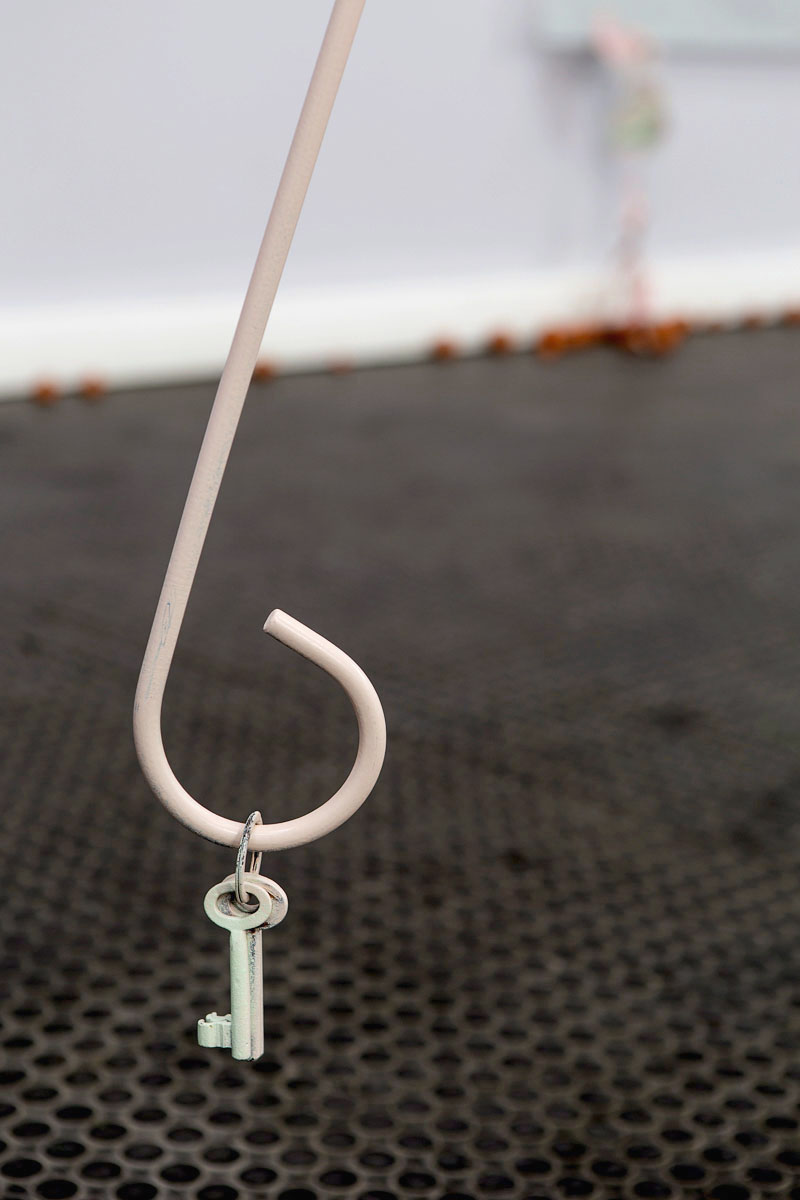

Bauhaus Octopus X, installaton detail, hand bent steel rods, latex calligraphy, chains

background: Tentaclelove, sandblasted painting on wire enforced glass with latex calligraphy

Compass

glazed ceramic, metal works from the tool store, 2017

Tentacle Love. Latex calligraphy, sand-blasted painting on steel enforced glass, latex coated steel rods for wall mounting, glazed ceramic hook. 2017

Neuromance Table

bent and welded steel rods, found glass, latex calligraphy, ceramic braids, 2017

Ulrike Buck curated by Marina Bobyleva

|